Northeast Boating

Capital Investment

Once seldom visited by boaters, Providence, Rhode Island, is transforming itself into a city worth discovering at the head of Narragansett Bay.

(Text below)

It was a quiet, gray morning as I paddled my kayak along the Seekonk River. Rounding India Point Park in Providence, with the shore about 30 feet to my right, I could see the wide mouth of the Providence River just beyond the grassy banks. I started to paddle over to a boat ramp when—thud!—I felt something smash against the bottom of my kayak.

My heart jumped. Then I felt two more quick taps near the back of the hull. The most rational explanation to my panicked mind was obvious: It was a sea monster—Rhode Island’s Nessie—trying to capsize me. Instead, I turned to see a wide-eyed cormorant pop out of the water a few feet away.

After a few deep breaths I gathered my wits and paddled to the ramp. My run-in with the cormorant hadn’t been the only encounter with waterfowl during my two-hour paddle along the Seekonk. I’d passed a half-dozen great blue herons and spooked scores of ducks. I was amazed at how such a grassy, tree-lined river scene could so completely hide the nearby downtown high-rises.

Not long ago, the only things I knew about Providence involved crooked politicians and the city’s large number of . . well, I’ll politely refer to them as gentlemen’s clubs. I just recently began to discover Providence because of my kids. It started when my wife Becky and I took 4-year-old Emma and 2-year-old Owen to the city’s Roger Williams Zoo—one of the Northeast’s best—where we all marveled at the animals. That led us to venture into other parts of the city—searching for burritos in the neighborhoods around Brown University and letting the kids play on the rope gym at India Point Park.

Now, as I pulled my kayak out of the water, a thought hit me like a speeding cormorant: I had been missing a lot. So I started exploring. What I found was an emerging waterfront, historic neighborhoods and a hip restaurant scene, as well as an event called Waterfire that just might make Providence the most romantic city in the Northeast. Yeah, that’s right—Providence.

Frank Duggan steered Sea Nile—a 26-foot Fortier powerboat—past the massive Fox Point Hurricane Barrier, underneath the yet-unused I-195 highway bridge and out into the wide mouth of the Providence River. It was a cool, late October day, and I was wearing a thick sweatshirt, with a wool hat in case it got really cold. But a bright, clear sky stretched overhead, and it was a great day for extending the boating season by one more weekend.

Come October, Rhode Island is one of the last refuges for New England boaters. While the leaves around my house near Boston had mostly turned brown and dropped, many of the trees lining the Providence River and northern Narragansett Bay were still green, with brushstrokes of yellows and reds mixed in. With the Providence skyline behind us and seagulls wheeling overhead, we kicked up our last wake of the year.

There may be people who know the Providence waterfront better than Frank Duggan, but I doubt it. As a lifelong resident of the area, he throws out facts and anecdotes about Providence like a history professor. He puts that knowledge to good use as the dockmaster and tour boat operator for Providence Piers. Right now it might look like an empty lot with a long dock on the western side of the Providence River, but Providence Piers could be the biggest thing to hit the city’s waterfront since Roger Williams, Providence’s founder, arrived in 1636. It is currently home to the 49-foot tour boat Duggan skippers and the Providence-to-Newport fast ferry. But developers Patrick and Gail Conley aim to make it the city’s first major waterfront development in recent memory—with plans that include an 88-slip marina, a hotel and condominiums.

As we motored on, the differences between East Providence (actually another city) and the working waterfront of the Providence River’s western shore became clear. The river’s eastern bank was tree-lined and dotted with condominiums, while to starboard loomed giant coal piles, storage buildings and freight cars. Just south of the LNG terminal, we cruised past the brand new Save the Bay Center on the western shore. Built on the site of the old Fields Point dump, the center is now used to teach people about the ecological importance of Narragansett Bay. Next we visited Pawtuxet Cove, where Duggan said Revolutionary War-era Rhode Islanders had their own run-in with the British several months before the much more famous Boston Tea Party. They sank a British revenue ship in what was arguably the first act of defiance by the colonists. “They don’t teach that in Massachusetts,” Duggan said with a laugh.

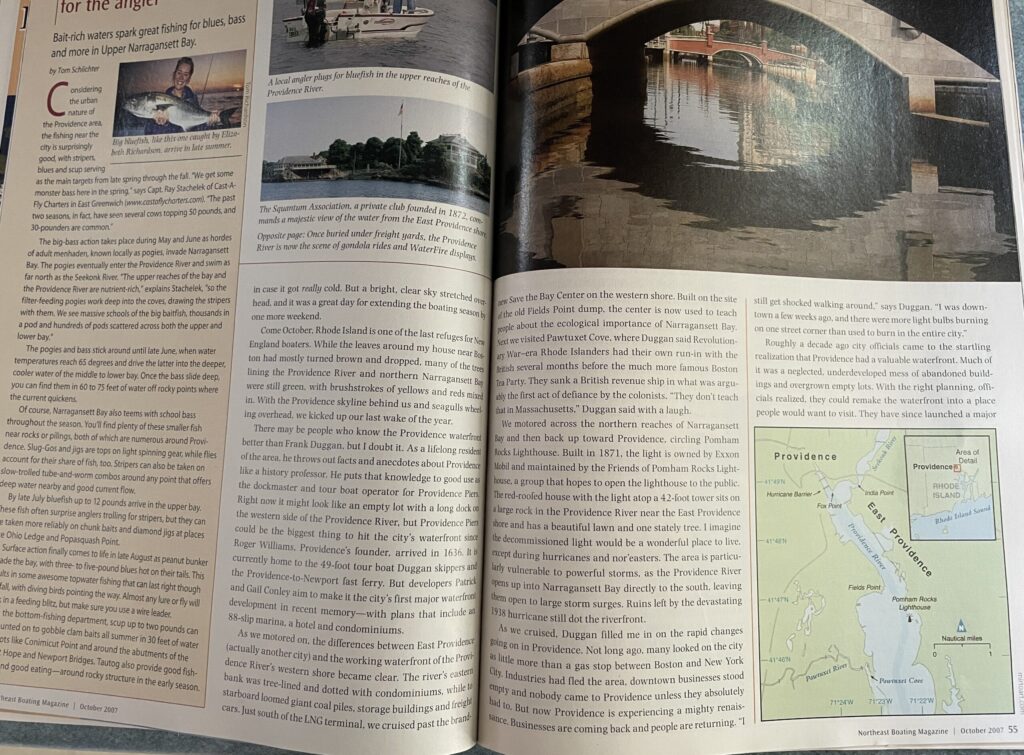

We motored across the northern reaches of Narragansett Bay and then back up toward Providence, circling Pomham Rocks Lighthouse. Built in 1871, the light is owned by Exxon Mobil and maintained by the Friends of Pomham Rocks Lighthouse, a group that hopes to open the lighthouse to the public. The red-roofed house with the light atop a 42-foot tower sits on a large rock in the Providence River near the East Providence shore and has a beautiful lawn and one stately tree. I imagine the decommissioned light would be a wonderful place to live, except during hurricanes and nor’easters. The area is particularly vulnerable to powerful storms, as the Providence River opens up into Narragansett Bay directly to the south, leaving them open to large storm surges. Ruins left by the devastating 1938 hurricane still dot the riverfront.

As we cruised, Duggan filled me in on the rapid changes going on in Providence. Not long ago, many looked on the city as little more than a gas stop between Boston and New York City. Industries had fled the area, downtown businesses stood empty and nobody came to Providence unless they absolutely had to. But now Providence is experiencing a mighty renaissance. Businesses are coming back and people are returning. “I still get shocked walking around,” says Duggan. “I was downtown a few weeks ago, and there were more light bulbs burning on one street corner than used to burn in the entire city.”

Roughly a decade ago city officials came to the startling realization that Providence had a valuable waterfront. Much of it was a neglected, underdeveloped mess of abandoned buildings and overgrown empty lots. With the right planning, officials realized, they could remake the waterfront into a place people would want to visit. They have since launched a major construction effort, much like Boston’s Big Dig, relocating a highway that once separated the waterfront from downtown in order to reconnect the shore with the rest of the city. Every place you go along the waterfront, you can see evidence of that work.

Yet, for a waterfront city, Providence doesn’t offer much to visiting boaters. Downtown Marina. behind the hurricane barrier, has a handful of transient slips. There are a couple more slips up the Seekonk River at the Oyster House Marina and at the East Providence Yacht Club. Other than that, boaters have to grab slips or moorings a few miles down the coast. That’s also where you’ll need to look if you want to gas up or have work done on your boat. But that’s changing. Besides the marina Providence Piers wants to put in, the city’s major planning document—a text called Providence 2020—calls for more access to be created for recreational boaters. Officials realize that lower Narragansett Bay is maxed out with marinas and that the upper bay and Providence area is the logical place for growth. Providing access to boaters will help business in Providence, and there are plenty of places nearby for boaters to enjoy.

Across the river from Providence Piers, cyclists pedal along the scenic 13-mile East Bay Bike Path, running from East Providence to Bristol. Within the next year, the bike path will cross the Seekonk River to India Point and into the city. At India Point Park people play soccer on the athletic fields, kids play on the kind of playground I wish we had when I was younger and a scenic walkway lines the waterfront, ending at the Community Boating Center, where residents who may not own their own boats can come to sail.

Just beyond India Point Park is the neighborhood of Fox Point, which has a laid-back, college-town feel about it. Fliers covering telephone poles advertise lectures, theater and music shows, activist meetings and restaurants. The aromas from Indian and Thai restaurants fill the air, and crowds sip cups of Java on the porch of the ultra-popular Coffee Exchange.

Follow the waterfront westward, and you come to the shore of the Providence River, just behind the hurricane barrier. The riprap near there is a popular shore-fishing spot, with urban anglers catching large stripers early in the season. Nearby, brand-new shops, clubs and restaurants represent the city’s changing face. When I was there this past spring, it was as if a completely different neighborhood had sprung up since my visit the previous fall. Oasis Café, with its panini sandwiches, had just opened. A few doors down, workers were sawing and hammering inside Steam Alley, a bar that was scheduled to open a few weeks later. Across the street a restaurant and lounge called Kurrents had just opened next to Downtown Marina, where I’d set out from with Frank Duggan last fall.

At Kurrents I sat outside on the large wooden deck, enjoying a sandwich and a beer and looking out over the river, gawking at beautiful powerboats pulling into the marina. The bartender, Lee Gemelli, told me the neighborhood was a popular spot on Friday and Saturday nights, with people packing Kurrents and the neighboring Hot Club and Fish Company Bar and Grille. A highway bridge walls off the neighborhood from downtown Providence, but Gemelli said the bridge should be gone within a year. He said the city also plans to extend the line of WaterFire braziers down the Providence River to their neighborhood.

Talk to local business people about what has spawned the city’s renaissance, and some may credit the extensive construction, others may mention all the new restaurants, but almost everyone will point to one thing: WaterFire.

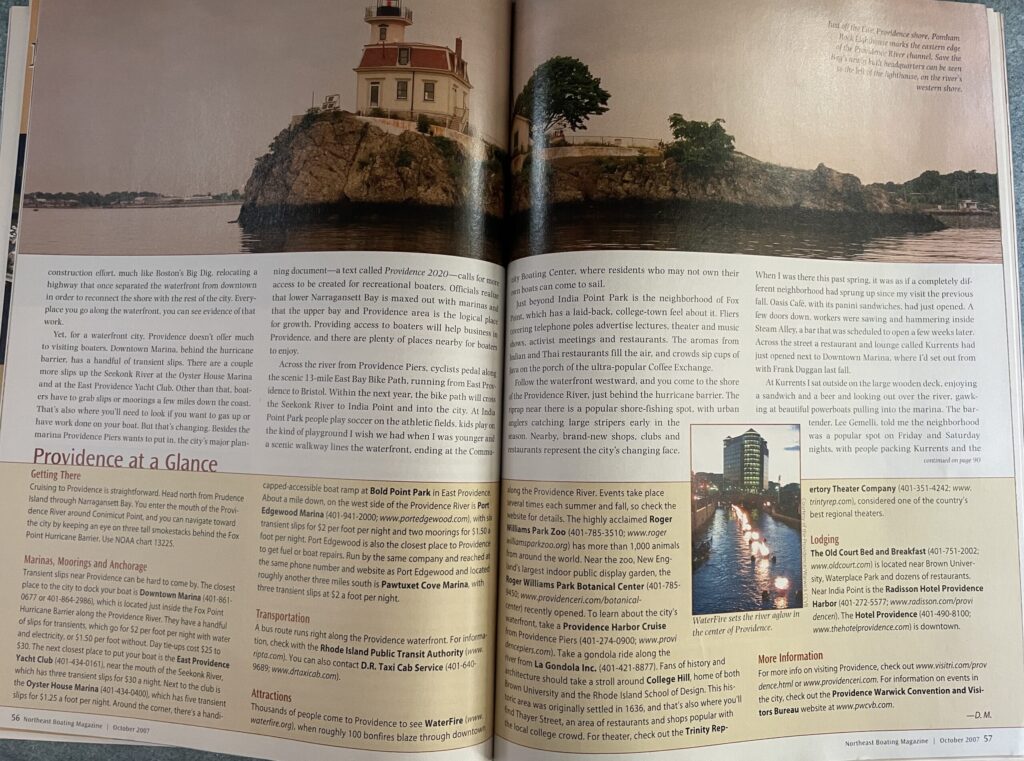

Several times each summer and into the fall, WaterFire organizers light fires in roughly 100 braziers running down the middle of the Providence River as it flows through the heart of the city. Artist Barnaby Evans started it more than 10 years ago to attract people to Providence River Park, which comprises more than a mile of scenic walkways and seven acres of open space along the river. “I only intended to do it once,” says Evans. “It was so popular, people wanted us to keep doing it.” Today, thousands flock to WaterFire. Evans shies away from claims that the display triggered the city’s renaissance, but, he says, if people come for WaterFire and discover all that Providence has to offer, that’s a good thing.

Not long ago, much of the Providence River was literally buried beneath the city, covered by industrial lots and freight yards and hidden from sight. But in recent years it has been uncovered and is now celebrated, part of the city’s facelift that was largely spearheaded by the colorful—and now infamous—former mayor Vincent “Buddy” Cianci. The still-popular mayor recently served jail time after a conviction for corruption and racketeering, but his influence in bringing the city into the limelight remains undeniable. Walk through the city and almost every plaque telling visitors about a new park or city feature bears Cianci’s name. That may be why many residents shrug their shoulders apologetically when the mayor’s name comes up, then sing his praises.

An hour before WaterFire lights up, the crowd builds along the river, visiting booths selling ice cream, crepes and Indian food. On the river, passing under a brick bridge, a man in a black-and-white-striped shirt poles a gondola while a couple onboard enjoys glasses of wine. Nearby, the city center’s tall buildings reflect the sunset’s reddish-pink glow.

During the day, small boats can access this part of the Providence River. Meandering up the waterway is a great way to see the city, and some businesses have docks that boaters can sometimes get permission to tie up to. Just be sure to keep an eve on the water level, as the river is shallow in spots, especially at low tide. When the fires are burning, though, the river is off-limits to the boating public.

As dusk settles in, small motorboats crewed by black-garbed workers slowly cruise upriver to light the fires. They begin as small flames, but soon become spectacular bonfires with quivering flames reaching six or seven feet above the water. Crackling sounds and the fragrant smell of burning cedar fill the air, and orange light reflects off surrounding stone walls and the faces of the crowd. People pose for photos. A wide-eyed girl chomps a caramel apple as she stares at the flames. A middle-aged couple snuggles in the glow.

A boat passes by with a man in the bow dressed in ghostly white, a black mask over his eyes and a pirate hat on his head. He tosses roses to the crowds alongside the river and onto the bridges overhead. At the city’s World War I monument nearby, people pose for pictures with ornately dressed human statues: a pharaoh. a Greek god and two gargoyles.

Down the road, crowds sitting at white tables around a jazz stage on Steeple Street (closed to traffic) applaud as a young musician plays his guitar while a keyboardist taps some background accompaniment.

Back at the river the burning fires along the water look like something out of medieval Europe. Adding to that feeling are candle lit chandeliers hung along the walkways beneath the Exchange Street and Waterplace Bridges. In fact, I have to think that if WaterFire were held in a major world city, it would be as much of a must-do experience as visiting the Eiffel Tower in Paris or walking the Charles Bridge in Prague. Of course, Providence doesn’t have the cachet of Paris or Prague . . . at least not yet.