Chatham Magazine

The Return of the Seals

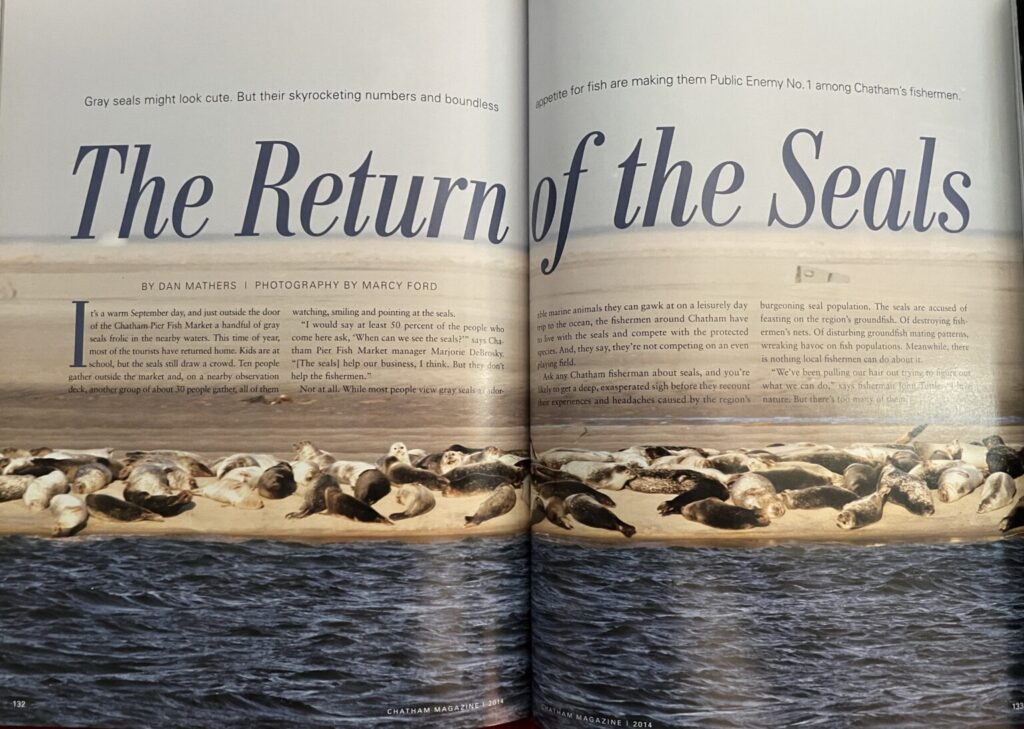

Gray seals might look cute. But their skyrocketing numbers and boundless appetite for fish are making them Public Enemy No. 1 among Chatham’s fishermen.

(Text below)

It’s a warm September day, and just outside the door of the Chatham Pier Fish Market a handful of gray seals frolic in the waters of Aunt Lydia’s Cove. This time of year, most of the tourists have returned home. Kids are at school; adults are at work. But the seals still draw a crowd. Ten people gather outside the market and, on a nearby observation deck, another group of about 30 people gather, all of them watching, smiling and pointing at the seals.

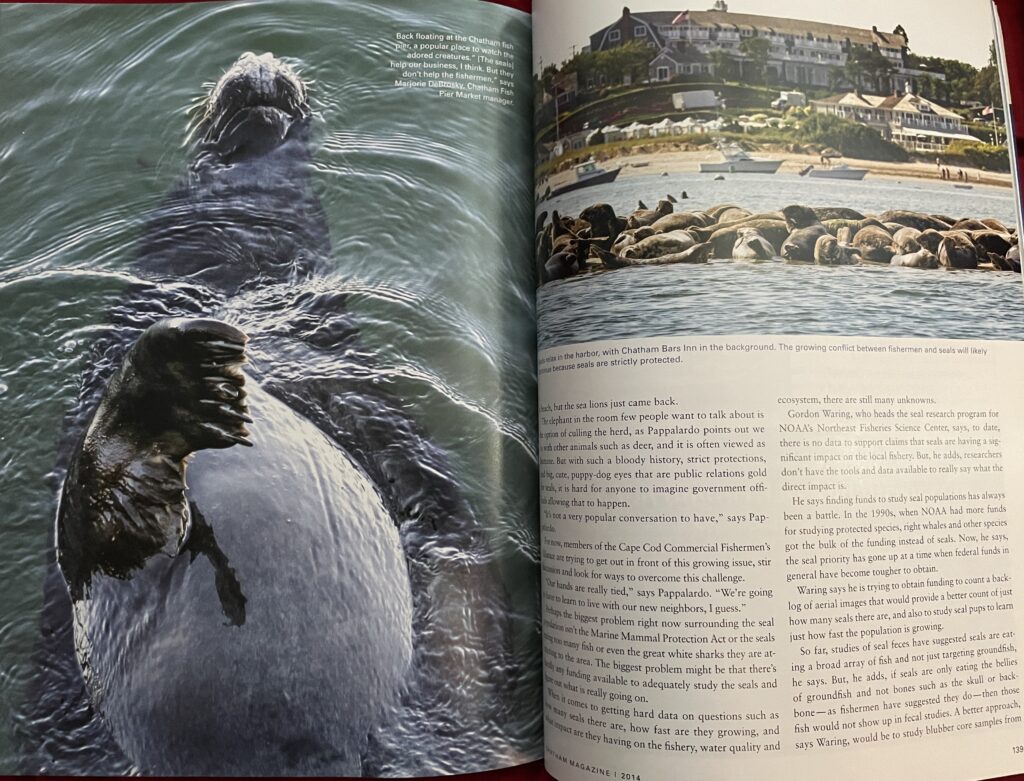

“I would say at least 50 percent of the people who come here ask ‘When can we see the seals?’” says Chatham Pier Fish Market manager Marjorie DeBrosky. “[The seals] help our business, I think. But they don’t help the fishermen.”

Not at all. While most people view gray seals as adorable marine animals they can gawk at on a leisurely day trip to the ocean, the fishermen around Chatham have to live with the seals and compete with the protected species. And, they say, they’re not competing on an even playing field.

Ask any Chatham fisherman about seals, and you’re likely to get a deep, exasperated sigh before they recount their experiences and headaches caused by the region’s burgeoning seal population. The seals are accused of feasting on the region’s groundfish. Of destroying fishermen’s nets. Of disturbing groundfish mating patterns, wreaking havoc on fish populations. Meanwhile, there is nothing local

fishermen can do about it.

“We’ve been pulling our hair out trying to figure out what we can do,” says fisherman John Tuttle. “I love nature. But there’s too many of them.”

Years ago, the gray seal population in the Northeast was almost completely wiped out. Until 1962, Massachusetts had a bounty program for seals driven mainly by fishing concerns. The hunting of seals was so complete that they were almost non-existent in the region by the time the Marine Mammal Protection Act was passed in 1972.

With the law strictly forbidding the harming or disturbing of seals, the population was left on its own to rebuild. But for years, any seal sighting was an exceptionally rare treat.

“When I started fishing [35 years ago] there were no seals around,” says Tuttle. “Never saw a seal. Never.”

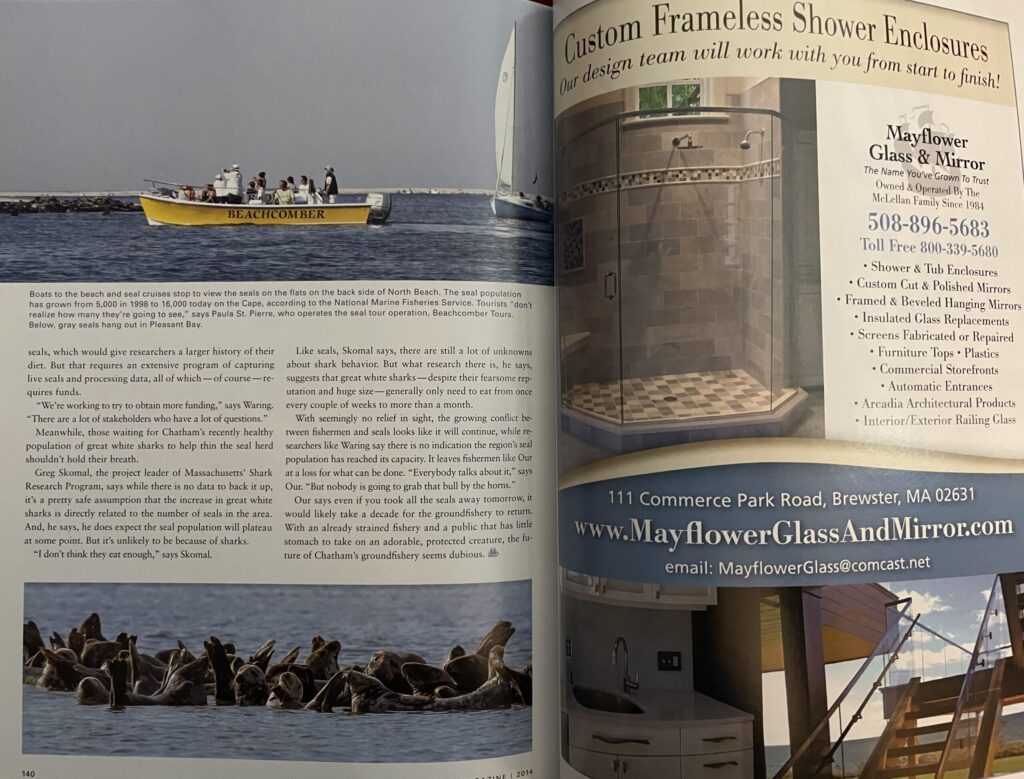

In the late 1980s, occasional seal sightings became more frequent, and by the late 1990s there were enough seals in the area to support seal tours. Paula St. Pierre started her seal tour operation, Beachcomber Tours, in 1998, when rough estimates from the National Marine Fisheries Service put the Cape’s seal population at around 5,000. Since then, she says, she’s watched the seal population “explode.”

Today, those rough estimates from the NMFS put the Cape’s seal population at over 16,000, much to the delight of tourists who, St. Pierre says, are constantly amazed at how many seals there are.

“They don’t realize how many they’re going to see,” she says.

But the seals’ success has come at a price, and the region’s fishermen say they’re the ones paying that price.

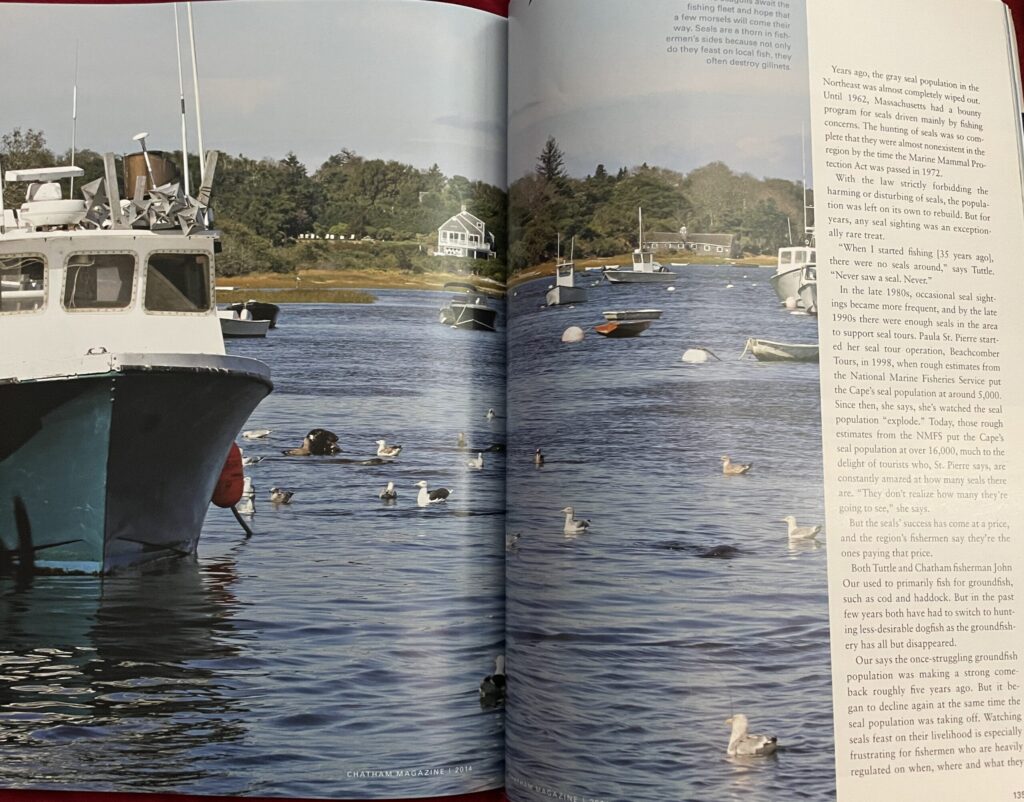

Both Tuttle and Chatham fisherman John Our used to primarily fish for groundfish such as cod and haddock. But in the past few years both have had to switch to hunting less-desirable dogfish as the groundfishery has all but disappeared.

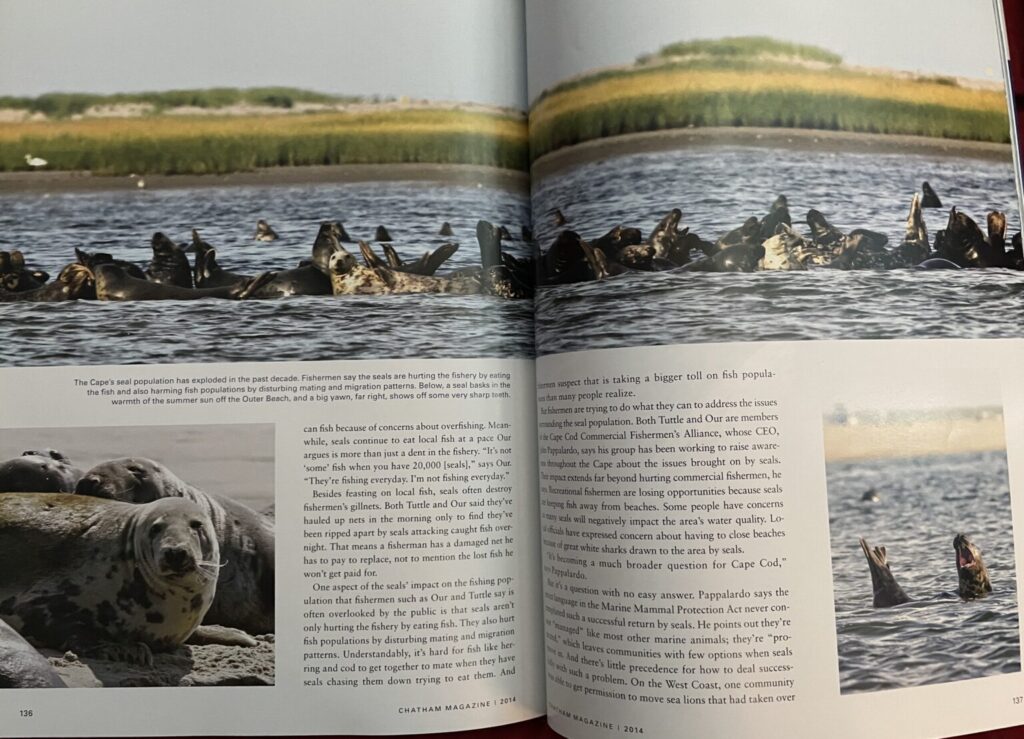

Our says the once struggling groundfish population was making a strong comeback roughly five years ago. But it began to decline again at the same time the seal population was taking off. Watching seals feast on their livelihood is especially frustrating for fishermen who, because of concerns about overfishing, are heavily regulated on when, where and what they can fish. Meanwhile, seals continue to eat local fish at a pace Our argues is more than just a dent in the fishery. “It’s not ‘some’ fish when you have 20,000 [seals],” says Our. “They’re fishing everyday. I’m not fishing everyday, but they do.”

Besides feasting on local fish, seals often destroy fishermen’s gillnets. Both Tuttle and Our said they’ve hauled up nets in the morning only to find they’ve been ripped apart by seals attacking caught fish overnight. That means fishermen have a damaged net they have to pay to replace, not to mention the lost fish they won’t get paid for.

One aspect of the seals’ impact on the fishing population that fishermen like Our and Tuttle say is often overlooked by the public is that seals aren’t only hurting the fishery by eating fish. They also hurt fish populations by disturbing mating and migration patterns. Understandably, it’s hard for fish like herring and cod to get together to mate when they have seals chasing them down trying to eat them. And fishermen suspect that is taking a bigger toll on fish populations than many people realize.

But fishermen are trying to do what they can to address the issues surrounding the seal population. Both Tuttle and Our are members of the Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance, the largest organization on the Cape dedicated to protecting marine resources and fishing interests. The alliance’s CEO, John Pappalardo, says his group has been working to raise awareness throughout the Cape about the issues brought on by seals. Their impact extends far beyond hurting commercial fishermen, he says.

Recreational fishermen are losing opportunities because seals are keeping fish away from beaches. Some people have concerns so many seals will negatively impact the area’s water quality. Local officials have expressed concern about having to close beaches because of great white sharks drawn to the area by seals.

“It’s becoming a much broader question for Cape Cod,” says Pappalardo.

But it’s a question with no easy answer. Pappalardo says the strict language in the Marine Mammal Protection Act never contemplated such a successful return by seals. He points out they’re not “managed” like most other marine animals; they’re “protected,” which leaves communities with few options when seals move in. And there’s little precedence for how to deal successfully with such a problem. On the West Coast, one community was able to get permission to move sea lions that had taken over a beach, but the sea lions just came back.

The elephant in the room few people want to talk about is the option of culling the herd, as Pappalardo points out we do with other animals such as deer, and it is often viewed as humane. But with such a bloody history, strict protections, and big, cute, puppy-dog eyes that are public relations gold for seals, it is hard for anyone to imagine government officials allowing that to happen.

“It’s not a very popular conversation to have,” says Pappalardo.

For now, members of the Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance are trying to get out in front of this growing issue, stir discussion and look for ways to overcome this challenge.

“Our hands are really tied,” says Pappalardo. “We’re going to have to learn to live with our new neighbors, I guess.”

Perhaps the biggest problem right now surrounding the seal population isn’t the Marine Mammal Protection Act or the seals eating too many fish or even the great white sharks they are attracting to the area. The biggest problem might be that there’s hardly any funding available to adequately study the seals and figure out what is really going on.

When it comes to getting hard data on questions such as how many seals there are, how fast are they growing, and what impact are they having on the fishery, water quality and ecosystem, all the questions have the same answer: We really don’t know.

Gordon Waring, who heads the seal research program for NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center, says, to date, there is no data to support claims that seals are having a significant impact on the local fishery. But, he adds, researchers don’t have the tools and data available to really say what the direct impact is.

He says finding funds to study seal populations has always been a battle. In the 1990s, when NOAA had more funds for studying protected species, right whales and other species got the bulk of the funding instead of seals. Now, he says, the seal priority has gone up at a time when federal funds in general have become tougher to obtain.

Waring says he is trying to obtain funding to count a backlog of aerial images that would provide a better count of just how many seals there are, and also to study seal pups to learn just how fast the population is growing.

So far, studies of seal feces have suggested seals are eating a broad array of fish and not just targeting groundfish, he says. But, he adds, if seals are only eating the bellies of groundfish and not bones such as the skull or backbone — as fishermen have suggested they do — then those fish would not show up in fecal studies. A better approach, says Waring, would be to study blubber core samples from seals, which would give researchers a larger history of their diet. But that requires an extensive program of capturing live seals and processing data, all of which — of course — requires funds.

“We’re working to try to obtain more funding,” says Waring. “There are a lot of stakeholders who have a lot of questions.”

Meanwhile, those waiting for Chatham’s recently healthy population of great white sharks to help thin the seal herd shouldn’t hold their breath.

Greg Skomal, the project leader of Massachusetts’ Shark Research Program, says while there is no data to back it up, it’s a pretty safe assumption that the increase in great white sharks is directly related to the number of seals in the area. And, he says, he does expect the seal population will plateau at some point. But it’s unlikely to be because of sharks.

“I don’t think they eat enough,” says Skomal.

Like seals, Skomal says, there is still lots we don’t know about shark behavior. But what research there is, he says, suggests that great white sharks — despite their fearsome reputation and huge size — generally only need to eat from once every couple of weeks to more than a month.

With seemingly no relief in sight, the growing conflict between fishermen and seals looks like it will continue, while researchers like Waring say there is no indication the region’s seal population has reached its capacity. It leaves fishermen like Our at a loss for what can be done. “Everybody talks about it,” says Our. “But nobody is going to grab that bull by the horns.”

Our says even if you took all the seals away tomorrow, it would likely take a decade for the groundfishery to return. With an already strained fishery and a public that has little stomach to take on an adorable, protected creature, the future of Chatham’s groundfishery seems dubious.

“If you’re trying to grow a field of corn,” says Our, “you can’t have a field filled with locusts.”