Cape Cod Magazine

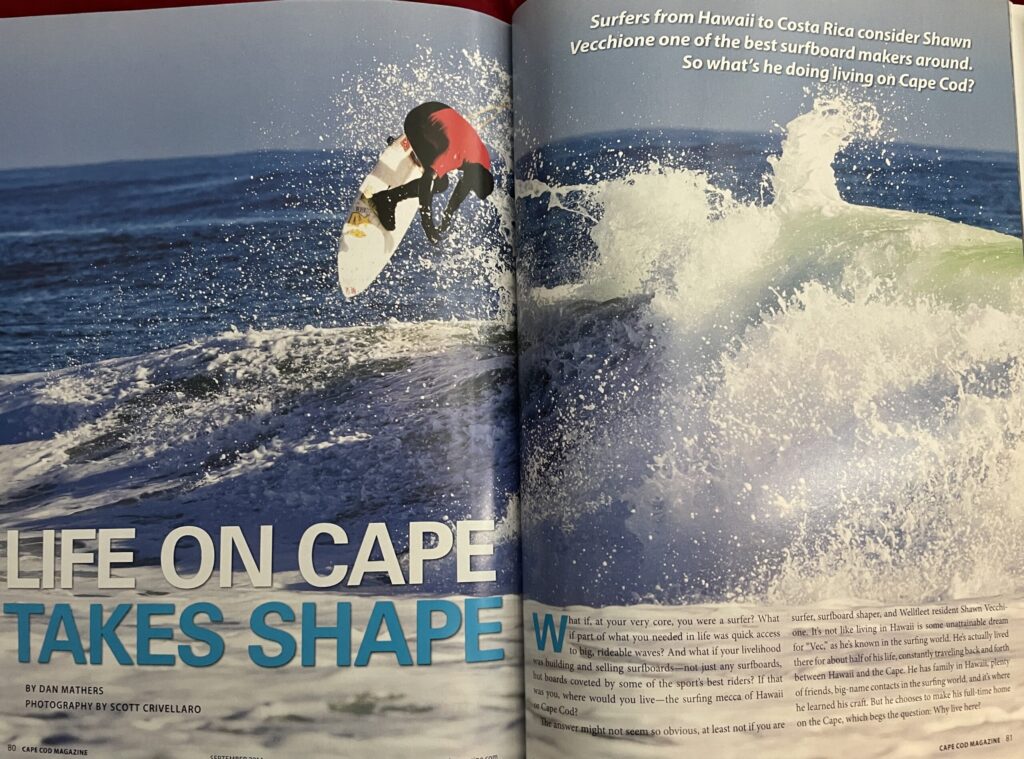

Life on Cape Takes Shape

Surfers from Hawaii to Costa Rica consider Shawn Vecchione one of the best surfboard makers around. So what’s he doing living on Cape Cod?

(Text below)

What if, at your very core, you were a surfer? What if part of what you needed in life was quick access to big, rideable waves? And what if your livelihood was building and selling surfboards—not just any surfboards, but boards coveted by some of the sport’s best riders? If that was you, where would you live—the surfing mecca of Hawaii or Cape Cod?

The answer might not seem so obvious, at least not if you are surfer, surfboard shaper, and Wellfleet resident Shawn Vecchione. It’s not like living in Hawaii is some unattainable dream for “Vec,” as he’s known in the surfing world. He’s actually lived there for about half of his life, constantly traveling back and forth between Hawaii and the Cape. He has family in Hawaii, plenty of friends, big-name contacts in the surfing world, and it’s where he learned his craft. But he chooses to make his full-time home on the Cape, which begs the question: Why live here?

“Yeah,” he says with a laugh, “I get that all the time.”

On the surface, the Cape might seem an unlikely home for one of surfing’s most respected surfboard builders. As a shaper – someone who designs and builds surfboards by hand – Vecchione, 42, has gained a reputation as perhaps the best on the East Coast. He runs Vec Surfboards and creates his boards in his Orleans shop, boards that have ridden the planet’s most famous waves and can be seen during pro and big-wave competitions. Somehow the Cape has wound up being home to a star of the surfing world. And it turns out that makes a lot more sense than you might think.

Vec Surfboards is housed in the corner of a small brick building in Orleans that is also home to a bagel shop and a real estate business. A couple of surfing posters hang in the window, and a small buoy leans outside the door. Inside, dark walls and a creaking wood floor make the shop feel less like a business and more like a clubhouse.

Leaning surfboards line the walls on the left side of the shop — from short, sporty foam boards that look like they’d be ripping waves in a Red Bull commercial, to a few classic, long wood boards that seem straight out of an early 1960s beach party movie. Near the door is a rack displaying wetsuits – a must for Cape surfers. To the right are displays for sandals and sunglasses that Vecchione says he is phasing out to focus on hard goods for surfboards and a clothing line that he and some friends are developing.

A large window on the back wall looks into Vecchione’s workshop, where people can watch him shaping a board. A fine coating of polyurethane dust coats the floor. Boards in progress hang on the wall. In the middle of the room stand two posts with U-shaped forks used for holding a board being shaped, either flat across or propped on its side inside the U while Vecchione works on its edges.

The shaping process starts with a blank canvas, which is usually a roughly 6-foot, rectangular polyurethane foam blank that looks a lot like a wall from a giant Styrofoam cooler. On the blank, Vecchione outlines the shape of the board, which depends on how big the surfer is and what type of waves he or she will be riding. He dons a Darth Vader-like respirator and begins molding the board, using tools such as planers, levels, a handsaw, a hacksaw, and sandpaper.

As a shaper, Vecchione is part carpenter, part engineer, part artist. He considers how he wants the water to flow through the bottom of the board as he is designing the underside. As he creates the deck — the top of the board where the surfer lays and stands — he thinks of where the board needs to be thicker or thinner. He then shapes the rails, or edges of the board, which will depend on the type of wave being surfed and how he wants the board to react. As the board takes shape, Vecchione looks much like a sculptor, repeatedly inspecting each inch, smoothing out each rough spot.

It’s an art form that he loves sharing with others. Vecchione recently started teaching people to shape their own boards at his shop. He shows them what they need to do and then lets them get the satisfaction of creating their own board. The enjoyment Vecchione gets from talking with surfers is part of what drives him, because surfing is often more than just surfing. It can be a lifestyle, and he’s seen many times how catching the surfing bug can be life-altering.

“It’s really rewarding,” he says. “From the Top 44 guy winning a contest to a kid who changes his life and is off the streets because he totally has the surfing bug because of his first surfboard, which was one of mine, it all makes me feel so good.”

Like much of Vecchione’s story, his journey to becoming a shaper was pretty unlikely. His dad is from Cape Cod, and his mom from Hawaii. He’s been traveling back and forth between the two places since he was a young kid, learning to surf when he was 14.

Somehow along the way, this surfer from Hawaii and Cape Cod became a snowboarder. A really good snowboarder. He was a pro snowboarder for Burton Snowboards, and was the first-pick hopeful for the U.S. Olympic team in 1990. But a back injury derailed his snowboarding career, and he moved back to Hawaii in 1991.

“For me, I always loved the ocean and surfing way more,” says Vecchione. “I knew I could make a career of snowboarding and that’s why I pursued it. But my heart wasn’t completely there. My heart was with surfing.”

He lived as a surf bum in Hawaii for a few years until a friend on Cape Cod suggested they open a surf shop. Together they opened the Boarding House surf shop in Hyannis and ran that for seven years, until Vecchione sold his half of the shop and moved back to Hawaii.

While spending his days surfing in Hawaii, the idea of shaping his own boards was far from Vecchione’s mind. He’d built a reputation in Hawaii as an excellent surfer who knew his stuff. But when a friend suggested he try making a board, it ended up changing his life. His first board came out well. Then he made another. Watching his friends ride the boards he made, having a great time on the waves, Vecchione became hooked.

“I was like ‘This is the best feeling ever,’” he says. “I was getting so much enjoyment watching people surf so well on this board and be happy. That went right to my heart.”

After making only a handful of boards, Vecchione had friends who were professional surfers asking him to make them boards. Soon he was making boards for people all over Hawaii.

As he honed his shaping skills, Vecchione got to work with two legendary shapers, Dick Brewer and Billy Hamilton. Brewer pioneered the tri-fin surfboard, the performance shortboard that the majority of surfers ride today. Hamilton, who in 1985 was voted one of the Top 25 most influential surfers in history and is the father of famed surfer Laird Hamilton, was designing big wave surfboards. Shaping with Brewer and Hamilton was like learning baseball from two Hall of Famers, and in no time Vecchione was turning out boards with the kind of know-how and experience that normally takes years to develop.

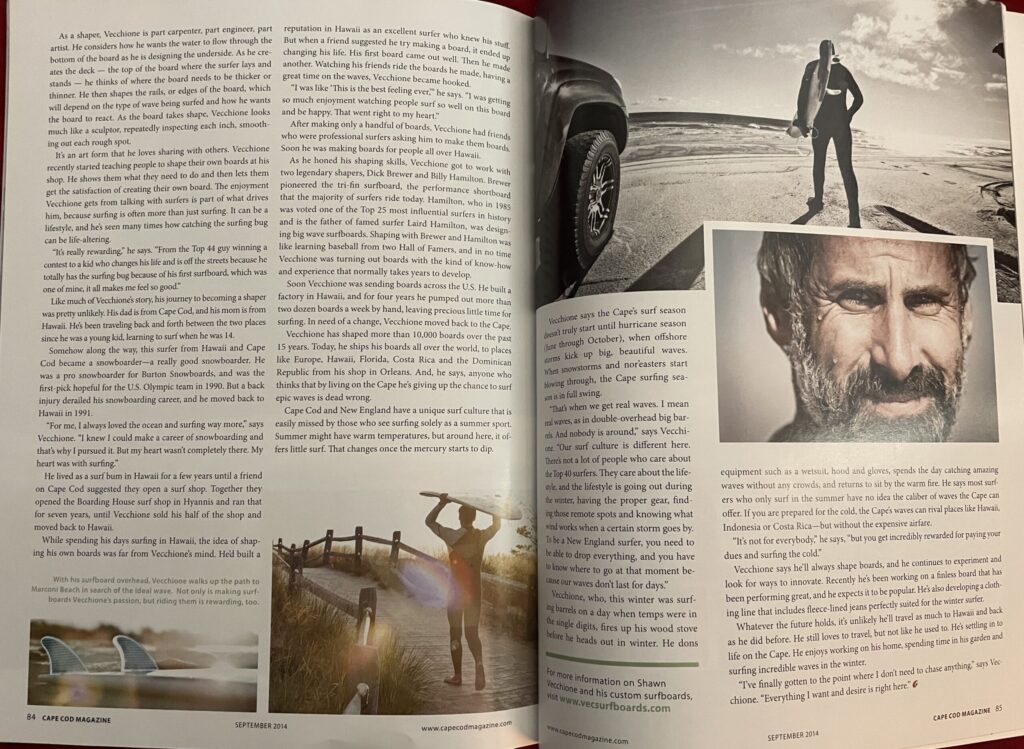

Soon Vecchione was sending boards across the U.S. He built a factory in??, and for four years he pumped out more than two dozen boards a week by hand, leaving precious little time for surfing. In need of a change, Vecchione moved back to the Cape.

Vecchione has shaped more than 10,000 boards over the past 15 years. Today, he ships his boards all over the world, to places like Europe, Hawaii, Florida, Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic from his shop in Orleans. And, he says, anyone who thinks that by living on the Cape he’s giving up the chance to surf epic waves is dead wrong.

Cape Cod and New England have a unique surf culture that is easily missed by those who see surfing solely as a summer sport. Summer might have warm temperatures, but around here, it offers little surf. That changes once the mercury starts to dip.

Vecchione says the Cape’s surf season doesn’t truly start until hurricane season (June through October), when offshore storms kick up big, beautiful waves. When snowstorms and nor’easters start blowing through, the Cape surfing season is in full swing.

“That’s when we get real waves. I mean real waves, as in double-overhead big barrels. And nobody is around,” says Vecchione. “Our surf culture is different here. There’s not a lot of people who care about the Top 40 surfers. They care about the lifestyle, and the lifestyle is going out during the winter, having the proper gear, finding those remote spots and knowing what wind works when a certain storm goes by. To be a New England surfer, you need to be able to drop everything, and you have to know where to go at that moment because our waves don’t last for days.”

Vecchione, who, this winter was surfing barrels on a day when temps were in the single digits, fires up his wood stove before he heads out in winter. He dons equipment such as a wetsuit, hood and gloves, spends the day catching amazing waves without any crowds, and returns to sit by the warm fire. He says most surfers who only surf in the summer have no idea the caliber of waves the Cape can offer. If you are prepared for the cold, the Cape’s waves can rival places like Hawaii, Indonesia or Costa Rica—but without the expensive airfare.

“It’s not for everybody,” he says, “but you get incredibly rewarded for paying your dues and surfing the cold.”

Vecchione says he’ll always shape boards, and he continues to experiment and look for ways to innovate. Recently he’s been working on a finless board that has been performing great, and he expects it to be popular. He’s also developing a clothing line that includes fleece-lined jeans perfectly suited for the winter surfer.

Whatever the future holds, it’s unlikely he’ll travel as much to Hawaii and back as he did before. He still loves to travel, but not like he used to. He’s settling in to life on the Cape. He enjoys working on his home, spending time in his garden and surfing incredible waves in the winter.

“I’ve finally gotten to the point where I don’t need to chase anything,” says Vecchione. “Everything I want and desire is right here.”